I've lost count of which week of lockdown it is, but I do know that it's Week 13 in the University calendar, which means two more weeks of semester to go and then it is the long vacation - or "the summer semester" depending how you reckon it. I have two MSc projects to supervise over summer, so I have some direct teaching to do, as well as plenty of preparation for my autumn semester modules.

This week I have been marking Final Year Project reports from various students on our BSc programmes, covering various different topics. It's been interesting to see what they have been up to in their projects, and as marking goes, they are enjoyably varied – more so than 50 exam scripts answering the same questions, though the similarity in that case has its own benefits.

This week also sees the publication (

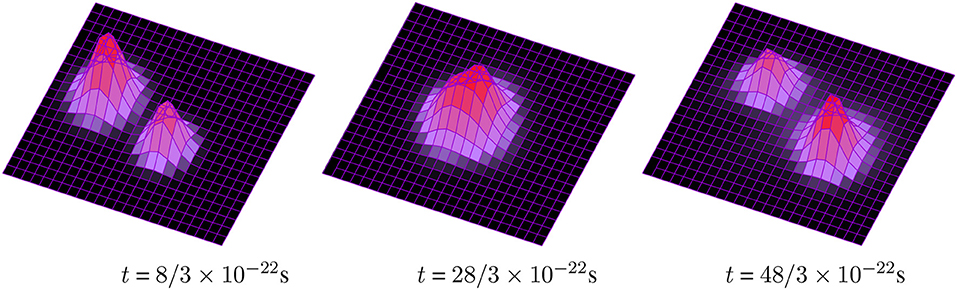

here) of a work done in a Final Year Project last year, by a student (Evan Cryer-Jenkins) working with me on a topic in Special Relativity - namely on the visual appearance of fast-moving objects. There are well known optical distortion effects that arise in Special Relativity thanks to a combination of length contraction, and the finite speed of light meaning that light has to leave different parts of an extended object at different times in order to arrive at ones eye at the same time. Evan, in this project looked at how such a distortion would appear to a two-eyed observer (or to two spatially-separated cameras) and how the two different images would not be able to be focused to a single image. In a way it's similar to looking at an object through a glass of water - each eye will see a fixed shape distorted in to two different shapes because of the different optical path taken to reach each eye. We also looked at what one might be able to infer (the distance and speed of the object) from the absolute and relative distortions.

We submitted the paper not much less than a year ago. The first referee reports came back giving us hope for acceptance if we made a few changes, and responded to the referees' points. The journal (Proceedings of the Royal Society) told us that a resubmission would be treated as a new submission, and so the published version is listed as being submitted in October. They are also quite on the slow side at doing things at that journal, not helped by the Coronavirus situation. Anyway - the paper was published this week. The same day, a journalist from Nature got in touch asking about the paper in order to run a story on it. That never happens to my nuclear physics research.

I also got, in the post, the fruits of my labour commenting on a book proposal for Cambridge University Press. This was a book on instantons which can be used to describe quantum tunnelling processes. I harbour a desire to use the technique to understand tunnelling in nuclear fission. If, after some effort at understanding the book, and further effort with implementing the calculations, running the code, processing and understanding the output, I may be able to write that up and see it published for all to see. I won't expect a journalist to get in touch with me, though. Perhaps I should think more often of writing for such a general journal as Proc Roy Soc A.

The picture shows me reading the book about instantons. Well, pretending to read, but activating the PhotoBooth app on my computer to take the picture.

_1.jpg/1200px-Imperial_War_Museum_North_-_WE_177_British_nuclear_bomb_(training_example)_1.jpg)