Roger Penrose was announced this morning as the winner of half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics, with the other half being shared equally between Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel. I will leave others to explain about the physics behind the prize award, since it is not really my area of expertise, but I wanted to post to mention the ways Penrose and his work has cropped up in my life

As a physics-interested schoolboy, I used to read through popular science books. Probably the first one I read, to the best of my memory, was Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time, which I got for Christmas the year it came out and was something of a must-read book for more or less anyone, though there was a kind of joke that few people finished it. I did finish it, and though I probably didn't understand it all, I found it at least readable and understood the words and got a sense always of the ideas being communicated, even if perhaps I didn't always gain a deep understanding.

Another one I read, while I was in the lower sixth (what we used to call Year 12) and applying to University, was Penrose's The Emperor's New Mind. I lent my copy to a girl I fancied and never got it back. I later learned that the rule of lending books to anyone was that you just go out and buy yourself another copy straight away. Anyway, I had finished the book, though I'm not sure I can remember too much of it in great detail now. It did make quite an impression on me at the time, though I think it was "harder" than Stephen Hawking's book and no doubt there was lots I didn't understand. I liked it for its broad sweep, combining ideas from physics to advanced mathematics, Turing machines, and on to somewhat more speculative stuff (which I didn't distinguish at the time, I suppose) to do with consciousness.

In December of 1991, when I was in the lower sixth and up in Oxford for an interview to read Physics and Philosophy I noticed that Penrose was giving a lecture for prospective students in Mathematics. In my interview for my place in college when asked if I had any questions I said I'd seen the advert for the talk and I asked if it would be okay if I went along to it. I'm not sure what they thought of my question - I guess I had no idea at the time that it would be perfectly fine for anyone to turn up and they wouldn't exactly be checking to see if I was really a prospective mathematics student. Anyway, I went along, and enjoyed the talk very much. Penrose talked about the famous Penrose tiles. I remember particularly a demonstration of how for certain near-symmetries you could make the symmetry almost perfect - as near to perfect as you liked, except not quite actual perfection - and he showed this by having two identical overhead projector slides with a 5-fold Penrose tiling, which he overlaid, and you could see the bands made in the thin regions where the pattern didn't quite repeat.

I don't think I have seen Penrose in person since then, 29 years ago, but I did get a copy of his huge "The Road To Reality" book as a 30th birthday present a bit later (in 2004). That's been sitting on my office shelves unread, I have to admit. I'm sure, as a practicing theoretical physicist, that I ought to be able to read and understand it, but even to me, opening it up it does look intimidating.

The other Penrose anecdote I have is that I found out at some point (perhaps the advent of wikipedia) that I share a birthday with several famous physicists, two of whom won Nobel prizes long ago). Now I can fill in another cell in this table:

The final Penrose-related thing links with my research: Earlier this year I co-published a paper with a bachelor's student based on his Final Year Project on the visual appearance of objects moving very fast (at an appreciable fraction of the speed of light). This is a new look at something which are either called Terrell Rotations, after the author who first got his name attached to it, or as the Penrose-Terrell effect, since Penrose independently submitted a paper on the same topic, published in the same year as Terrell. Even more properly, it can be called the Lampa-Terrell-Penrose effect, since Lampa published it first, in a paper that wasn't so widely known.

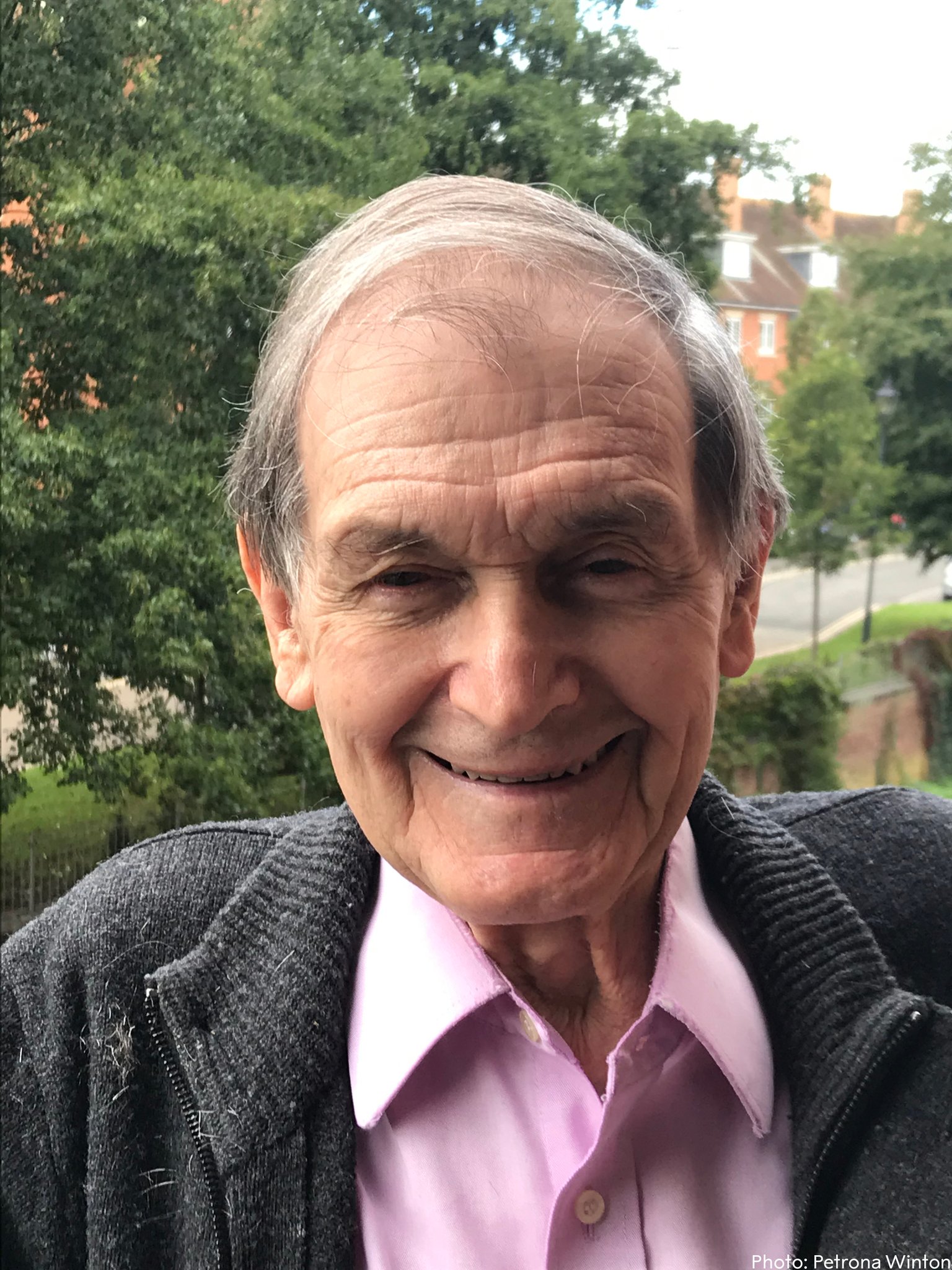

Here's a picture of Penrose, which he sent to the Nobel Committee from his house in Oxford this morning